On March 16, 2021, Modern Machine Shop launched a new podcast series, “Made in the USA.” The show is a six-part documentary-style series that strives to answer questions about the past, present and future of American manufacturing through exclusive interviews with world-class economists and manufacturing leaders.

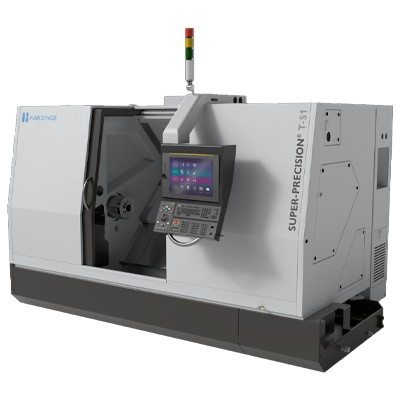

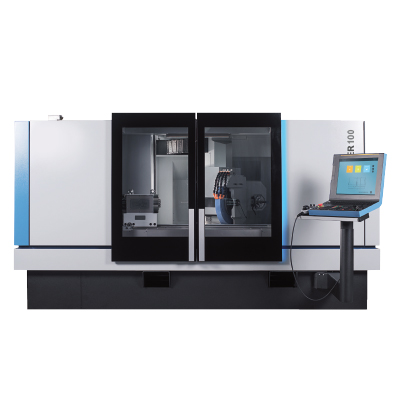

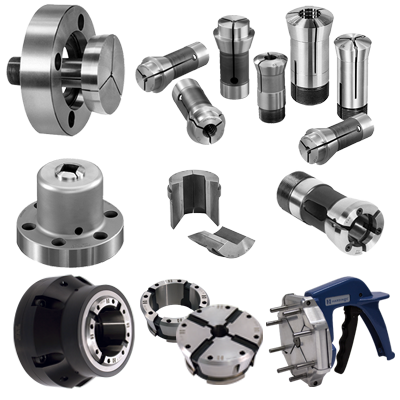

“Made in the USA” uncovers the hidden history of how manufacturing in the United States arrived at its current state and lays out where it can go from here. The series is sponsored by Hardinge who recently announced their plans to shift the manufacturing of its milling and turning machining center solutions from the Hardinge Taiwan plant to its plant in Elmira, NY, USA.

Episode 1 of Made in the USA Podcast is fascinating. It answers the question, “How did manufacturing in the US get to this place?” It examines manufacturing issues related to trade policy, global supply chains, education, automation and our ability to produce skilled workers.

Along with the moderators, Pete Zelinski and Brent Donaldson, guest speakers include: Robert Atkinson, President, Information Technology & Innovation Foundation, Mike DiMarino, President, Linda Tool, Susan Houseman, Vice-President and Director of Research at the Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, Scott Smith, Group Leader, Intelligent Machine Tools, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, and Doug Woods, President, The Association for Manufacturing Technology (AMT).

Scott Smith, Oak Ridge National Laboratory: “Moving the jobs to China didn’t kill the jobs. It just killed them in the US.”

Daron Acemoglu, MIT: “Japan, South Korea and Germany have increased their share of international trade in manufacturing. They have continued to make inroads in manufacturing growth. How did they do that?”

Here are snippets from the podcast.

When the US was the Manufacturing World Leader

Doug Woods: During World War Two, the US had a rapid ramp up of manufacturing of relatively complicated pieces of mechanized devices, you know, combinations of electronics and manufactured components and systems going into tanks and planes and vehicles being used in different parts of the transportation system. Throughout the 1950s, and 1960s, the United States was still the global leader in the machine tool industry.

As we got into the ‘70s and ‘80s, we got into kind of the period of leveraged buyouts and mergers and acquisitions, it was a lot about roll-ups. And what you saw was, the machine tool industry became kind of a victim of that process. And when I say a victim of the process, what ended up happening was a diametrical change from focusing on the core technology, focusing on innovation, focusing on innovating the next great product that solves a problem, to taking care of meeting a quarterly number, getting a return on the leveraged buyout, so the organization could be flipped again.

The Gradual Shift to Asia

During this time, they (Asian countries) were investing in their manufacturing technology and machine tool technology. And when we were unable to — here in the U.S. — focus on delivering high-quality products that were easy to use, with a customer-centric focus, the Asian countries were coming in and filling that void.

People needed to have stuff in their factory to make new products, and so they turned to whatever place they could start to find solutions. That was kind of the start of the evolution of the Asian machine tool market getting a really big foothold into the US market, which was an enormous change for decades to come.

Moderator Pete Zelinski: We have an impression that producers of manufacturing equipment from outside the US — Asian machine tool builders — that they made their way in because of price, that they undercut US machine tools because they were cheap. Doug doesn’t remember it that way. They made their way in because they were available.

Moderator Brent Donaldson: Of course, there were other factors influencing the shift taking place during this time. The power and influence of unions was changing, investments in research and development were shrinking, tax reform in the 1980s eliminated a tax credit that US manufacturers received when they invested in new equipment. So during this period of time, really the entire trajectory changed.

2000-2010 – Job Losses Add Up

Robert Atkinson: What happened to US manufacturing, really starting around the year 2000, was a very serious and long-term structural decline, largely due to competition from foreign nations and offshoring, a lot of that due to China…. over 50,000 manufacturing firms went bankrupt in the 2000s. Either they closed down, or they shrank or they move just wholesale moved operations offshore. Between the years 2002 and 2010, the economy lost 13 times as many manufacturing jobs as it did the previous decade. On average, more than 1,200 manufacturing jobs were lost every day for 10 years, the net loss of manufacturing firms and facilities amounting to 66,000 manufacturing sites closed. In other words, on each day since the year 2000, for 10 years, America had on average 17 fewer factories, plants and machine shops than it had the previous day.

But the biggest change was really allowing China to join the WTO with very, very few guardrails. So, for example, there was no provision in there around currency manipulation. The Chinese manipulated their currency, they kept their value of their currency very low, which meant that imports from China to the US were essentially subsidized, if you will, and exports to China were taxed, that would be such an equivalent of that.

Scott Smith: This was — so in the timeframe that you talk about, this is when a lot of companies were relocating manufacturing from the US to China, right? And they were primarily doing that with an argument that the wage rate there was lower. I mean, this is an argument that is commonly made, you know, “we can’t compete against those low wages, it’s just natural,” and we were going to be a post-industrial society. So we would do all the design work here, and then the manufacturing would go to where the low labor rates were. I think this was this was a conscious decision. Now, I think that’s completely wrong. I think we shouldn’t have said, “we can’t compete with low wages,” we should have said something like, “given the fact that there’s a wage difference, how do we compete?” That’s a completely different mindset.

If it’s just low wages, then surely that effect must have happened in Germany also, but that does not seem to be the case. The US almost completely lost the production of machine tools. Germany didn’t, Japan didn’t, Switzerland didn’t. Those are not low-wage countries. Why didn’t they lose their machine tool industry?

Susan Houseman: I’ll say many decades, at least up into the very early 2000s — it looked like manufacturing, real output growth was keeping pace with that in the economy overall.

The statistics and data, which were typically published at the aggregate level for all of manufacturing, were masking a lot of weaknesses in most industries. And that one industry — namely the computer and electronics products industry — was really accounting for the apparent robust growth in both output and productivity in the economy. If you broke out what I’ll call for shorthand, “the computer industry,” really suddenly the output growth in the rest of manufacturing didn’t look so good. And of course, there’s still variation. But the computer industry was really an off the charts outlier.

Mike DiMarino: We really are run by financial engineers in this country. Why? Greed. I mean, simple, simple greed. Yeah, you know, they stepped over a dollar to pick up a dime. So people used to buy stock in a company because of their integrity, because of what they could do. Now they buy it based on the growth that it can have in share price and the yield they can get out of it.I mean, everybody wants to make money, let’s face it.

Moderator Brent Donaldson: Okay, so Mike is great to end on because his perspective lines up with what Doug Woods was saying at the beginning. Treating manufacturing companies as financial instruments, instead of valuing them for what they make, is exactly what set us on a certain path. Let’s say it’s a path that we didn’t have to take.

Listen to this podcast in its entirety. The podcast series is available Apple Podcast, Google Podcast, Spotify, and Soundcloud.